The financial institution in brief:

Rabobank is a bank by and for customers, a cooperative bank, a socially- responsible bank. Our aim is to be market leader across all financial markets in the Netherlands. We are also committed to being a leading bank in the field of food and agri worldwide.

Rabobank is an international financial services provider operating on the basis of cooperative principles. It offers retail banking, wholesale banking, private banking, leasing and real estate services. As a cooperative bank, Rabobank puts customers’ interests first in its services. It serves approximately 8.7 million clients around the world. Rabobank Group is comprised of Coöperatieve Rabobank U.A. (Rabobank) and its consolidated subsidiaries in The Netherlands and abroad. It is committed to making a substantial contribution to welfare and prosperity in the Netherlands and to feeding the world sustainably.

We put the interests and ambitions of our customers and members first. With nearly two million members, we are one of the largest cooperatives in the Netherlands. And our members are more than just customers. They have a voice in deciding the bank’s strategic course.

Our commercially independent local Rabobanks form the most finely-meshed banking network in the Netherlands. They serve millions of Dutch retail and wholesale customers with a full range of financial services. We are market leader in the Netherlands in a number of segments.

Why use natural capital thinking?

Dairy farming is the largest consumer of land in the Netherlands. This means that the way the dairy farming industry treats the landscape has a significant impact on the habitat of flora and fauna. Pressure on revenues has compelled individual farms to increase the size of their farms, thereby increasing its impact on nature and the environment.

Effective management of the landscape by dairy farmers can significantly increase the chances of survival of species which are dependent on the agricultural landscape. Increasing biodiversity has also a direct impact on farms. Dairy farmers depend on natural resources, including fertile soil, sufficient and clean groundwater, and the availability of minerals. The promotion of functional biodiversity such as an abundance of soil organisms contributes to a living, healthy soil and facilitates optimum productivity. ‘Farming with nature’ helps to protect the natural capital essential to the farm’s future, and reduces dependence on external resources such as fertilisers, crop protection products and medication.

There is a growing interest among politicians and the public in the decline in biodiversity (that arises due to scale increase, eutrophication, land reparcelling, earlier and more often cut grassland, and a decrease in herbs in grasslands). The challenge for the dairy sector is to ensure continuity of farming – also in terms of availability of natural resources – while at the same time reducing the burden on the environment and strengthening the landscape in order to retain the social acceptance and be viable in the long term.

Friesland Campina, Rabobank and WNF (the Dutch chapter of WWF) are seeking to help restore biodiversity in agriculture. They aim to promote this goal by developing new revenue models in the supply chain. A second objective is to develop a metric to quantify any efforts by dairy farmers to improve biodiversity both on their own farms and beyond. This approach aims to create a tool which makes it possible to quantify biodiversity results and can also be used to reward dairy farmers through supply chain partners and other stakeholders.

For the Monitor, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) will be developed, to measure the influence of individual dairy farms on biodiversity on the farm and beyond. This ensures a standardised system. In addition to providing a metric for assessing the impact of the environment, the Monitor proposes specific measures such as increasing the amount of permanent grassland to improve biodiversity. Several criteria are set for the selection of KPIs, which are all based on integrality and measurability in order to be able to compare dairy farms with each other and compare farms over a period of time.

The process of developing the Biodiversity Monitor centred on the input of and interaction between theory and practice. During the development process, FrieslandCampina, Rabobank and WNF worked closely with dairy farmers, researchers and agricultural environmental organisations and preservation societies. A series of feedback meetings were scheduled to gather input from other stakeholders in the supply chain, including other dairy farms.

What were the outcomes of the assessment?

Firstly, a conceptual framework for ‘Biodiversity for Dairy Farming’ was developed, in which the term biodiversity is operationalised for dairy farming.

Four pillars arose from this framework: functional agrobiodiversity, diversity of landscape, diversity of species, and regional biodiversity. KPIs were developed with further research into existing databases and surveys. Potential measures, opportunities and action perspectives were further developed together with four agricultural nature management groups. The stakeholder dialogue coincided with these studies. Advisers and dairy farmers were regularly consulted, with the input mainly focusing on testing the framework, evaluation of KPIs and assessing measures which impact the KPIs. Currently, a prototype is developed. It presents the results of three sample farms, describes opportunities for improving biodiversity and details the interrelationship between the KPIs and biodiversity.

A key consideration when it comes to including or not including KPIs is whether a KPI can offset other KPIs. For instance, ‘percentage of grassland’ is eliminated as it is strongly related to ‘percentage of permanent grassland’. The second KPI has a larger value when it comes to improving biodiversity.

The KPIs are not applied individually; they balance each other out. By implication, all KPIs are required for biodiversity. For instance: the KPI ‘Percentage of protein produced on the farmer’s own land’ is an important KPI for Pillar 1 (‘Functional agrobiodiversity’), but can also serve as an incentive to increase grassland production per hectare, when in fact this could have a negative impact on biodiversity. By including the KPI ‘Nitrogen surplus in the soil’ and a KPI for ‘Herb-rich grassland’ in the set of KPIs, this potential negative side effect is offset.

Next steps

For application in practice, the ‘optimum environmental values’ must be determined, along with the ‘threshold values’. It is important, however, that the optimum level is determined in relation to all other indicators. Optimum environmental values show the most ideal situation from a biodiversity perspective. Threshold values indicate that a positive effect on biodiversity can be expected. Ideally speaking, all threshold values together should indicate a basic quality for a biodiverse dairy farm. The optimum environmental values will be further detailed in the follow-up to this project.

The applicability of the integrated set of indicators also needs to be assessed against the usability for dairy farmers in practice. Of particular importance is the check for a specific cohesion between the various KPIs. This is the only way to ensure that performance on the set of KPIs will actually result in an improvement of conditions for greater biodiversity. In addition to usability in practice, a comparison must be made of the performance of the KPIs and the actual level of biodiversity on and around the farm.

Another key aspect during the follow-up process is to further communicate the concept, involve other parties in the further development, and establish an organizational structure which facilitates the implementation of the Biodiversity Monitor for Dairy Farming as an independent standard.

Read through the other Finance Sector Supplement case studies here.

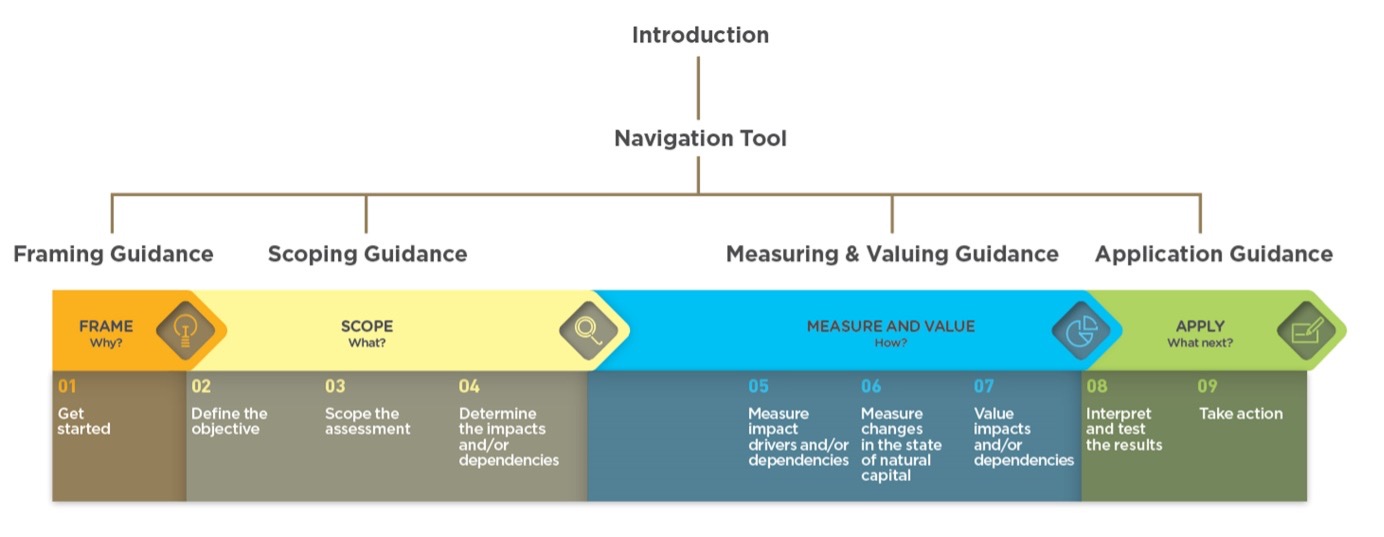

This case study support the Connecting Finance and Natural Capital project; brought together by the Natural Capital Coalition, the Natural Capital Finance Alliance and the VBDO.